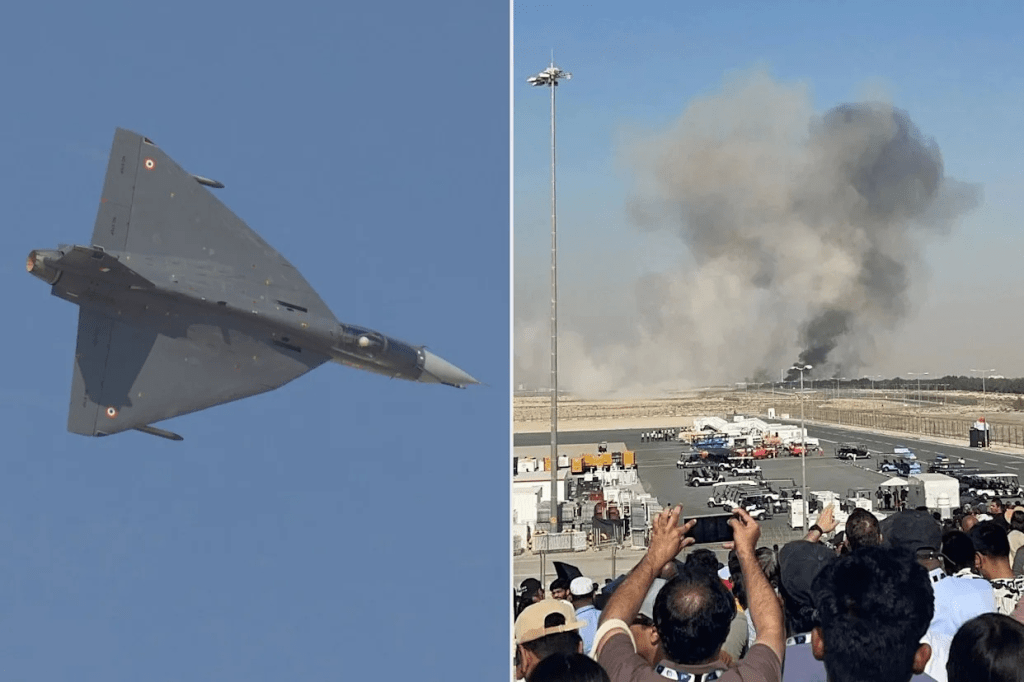

On 21 November 2025, an Indian Air Force HAL Tejas light combat aircraft crashed during a flying display at the Dubai Airshow, killing the pilot and sparking an international discussion about safety, aircraft reliability, and human performance in high‑G environments (Al Jazeera, 2025; Reuters, 2025; Simple Wikipedia, 2025). This incident underscores how acceleration, G forces, and phenomena such as the push–pull effect remain central to understanding risk in modern fighter operations (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; Metzler, 2020).

The Dubai Tejas Crash

Witness reports and video recordings indicate that the Tejas was performing an aerobatic maneuver at low altitude at Al Maktoum International Airport when it entered a steep nose‑low attitude, descended rapidly, and impacted the ground in a fireball near the airfield perimeter (Al Jazeera, 2025; Simple Wikipedia, 2025). Emergency responders quickly extinguished the post‑impact fire, but the pilot sustained fatal injuries and no successful ejection was observed (Reuters, 2025; Times of India, 2025). As of this writing, an Indian Air Force court of inquiry and civil aviation authorities are examining flight data, maintenance records, and human‑factor aspects to determine whether technical failure, control‑system issues, spatial disorientation, or G‑related incapacitation contributed to the crash (Economic Times, 2025; The Diplomat, 2025).

Tejas Performance and the G Environment

The HAL Tejas is a lightweight, highly agile multirole fighter with a high thrust‑to‑weight ratio and fly‑by‑wire controls, designed to execute rapid changes in attitude and flight path typical of modern air combat and airshow displays (AlphaDefense, 2023; Grokipedia, 2025). The aircraft structure and flight control system allow maneuvering in the neighborhood of +8 to +9 G and moderate negative G, placing significant physiological demands on pilots, especially during tight turns, vertical manoeuvres, and rapid transitions between nose‑low and nose‑high attitudes (AlphaDefense, 2023; Aircraft Wiki, 2024). In a densely constrained airshow “box,” pilots often combine high angle‑of‑attack manoeuvres, steep pull‑ups, and descending passes, creating complex acceleration profiles where even brief lapses in G‑protection technique can have serious consequences close to the ground (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; StatPearls, 2015).

Acceleration and G Forces in Fighter Flight

In aviation medicine, “G” is a measure of acceleration relative to Earth’s gravity, commonly expressed along the head‑to‑foot axis as +G_z (head‑to‑foot) and -G_z (foot‑to‑head) (StatPearls, 2015). At +9 G, a pilot’s effective body weight increases ninefold, dramatically increasing the hydrostatic gradient between the heart and the brain and promoting blood pooling in the lower extremities (StatPearls, 2015). If unmitigated, high +Gz can produce a progression from grey‑out, to blackout, to G‑induced loss of consciousness (G‑LOC), typically lasting several seconds and often followed by a period of confusion or almost‑loss‑of‑consciousness (A‑LOC) in which situational awareness and fine motor control are impaired (Sky Combat Ace, 2021; Whinnery & Forster, 2015, as cited in StatPearls, 2015). Anti‑G suits, pressure garments, and a well‑executed anti‑G straining maneuver (AGSM) raise tolerance, but case‑control data from high‑performance jets such as the F‑15, F‑16, and A‑10 show that inadequate AGSM, fatigue, and low baseline G‑tolerance remain major contributors to G‑LOC events (Manning & Eiken, 2005).

The Push–Pull Effect

Beyond simple high +G exposure, the push–pull effect (PPE) describes a rapid transition from relative under‑loading or negative Gz to high positive Gz, which markedly reduces the pilot’s tolerance to +G and increases the risk of G‑LOC or A‑LOC (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; Mallett & Young, 1994). During the “push” phase, blood shifts toward the head, and cardiovascular reflexes tend to reduce systemic vascular resistance; when followed almost immediately by a strong “pull” into +Gz, these reflex adjustments can blunt the body’s normal compensatory response, so that a G level that would otherwise be tolerable becomes incapacitating (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; Metzler, 2020). Centrifuge and inflight studies have shown that more negative pre‑exposure and longer durations of relative under‑loading further decrease subsequent +Gz tolerance, and that AGSM and G‑suits can only partially offset this vulnerability, particularly when acceleration onset rates are high (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; Singh et al., 2011).

A well‑publicized F‑16 mishap illustrates the operational danger of PPE. In that case, the pilot transitioned from approximately −2.06 Gz to +8.56 Gz in less than five seconds, after which flight data and cockpit recordings showed minimal control input for several seconds, followed by an unsuccessful late recovery before ground impact (Metzler, 2020). The accident investigation board concluded that the pilot experienced G‑LOC or severe A‑LOC due to the push–pull profile, highlighting that even experienced aircrew in front‑line fighters can be unexpectedly incapacitated when exposed to rapid G reversals (Metzler, 2020). Surveys and mishap statistics from multiple air forces suggest that a significant fraction of high‑performance pilots experience at least one G‑LOC or A‑LOC episode during their careers, reinforcing PPE as a persistent human‑systems risk in modern tactical aviation (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; StatPearls, 2015).

Tejas, Airshows, and Human Factors

At this stage, investigators have not released a final causal determination for the Dubai Tejas crash, and any attempt to attribute it specifically to G‑LOC or the push–pull effect remains speculative and inappropriate from a safety‑analysis standpoint (Economic Times, 2025; The Diplomat, 2025). Nonetheless, airshow routines in agile fighters routinely involve steep nose‑low segments, low‑altitude passes, and aggressive pull‑ups, which are precisely the manoeuvre types that can produce rapid G transitions and challenge pilot G‑tolerance margins, particularly in hot environments, under fatigue, or when the display sequence is tightly compressed (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; Safety Matters, 2025). For safety professionals and aerospace physiologists, the Tejas mishap serves as a case‑based reminder that structural capability and flight‑control agility must be matched by robust human‑systems integration: selection, training, physiological monitoring, and display‑profile design that respect the limits of the human cardiovascular system.

Ultimately, the loss of the Tejas and its pilot at Dubai is both a national tragedy and a global human‑factors lesson. As modern fighters achieve ever higher G capability and faster onset rates, acceleration management, understanding of PPE, and disciplined G‑protection must remain central pillars of flight‑safety programs, especially in visually impressive but physiologically unforgiving environments like international airshows (Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 2001; Metzler, 2020; StatPearls, 2015).

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, November 21). India’s Tejas fighter jet crashes at Dubai Airshow, pilot dies. https://www.aljazeera.com%5Breuters +1]

AlphaDefense. (2023, August 17). LCA Tejas. https://alphadefense.in%5Balphadefense%5D

Aircraft Wiki. (2024, October 28). LCA Tejas. https://aircraft.fandom.com/wiki/LCA_Tejas%5Baircraft.fandom%5D

Economic Times. (2025, November 21). Tejas pilot dead: IAF launches inquiry into Dubai Air Show 2025 crash. https://economictimes.com%5Beconomictimes%5D

Grokipedia. (2025, November 27). HAL Tejas. https://grokipedia.com/page/HAL_Tejas%5Bgrokipedia%5D

Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine. (2001, June 29). Push–pull effect. https://indjaerospacemed.com/push-pull-effect%5Bindjaerospacemed%5D

Mallett, W. M., & Young, J. M. (1994). The “push–pull effect.” Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 65(8), 699–703. (Abstract available at PubMed).[pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih]

Manning, M. R., & Eiken, O. (2005). A case‑control study of 78 G‑LOCs in the F‑15, F‑16, and A‑10. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 76(10), 1005–1012. (Abstract available at PubMed).[pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih]

Metzler, M. M. (2020). G‑LOC due to the push–pull effect in a fatal F‑16 mishap. Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance, 91(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.3357/AMHP.5461.2020%5Bpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih%5D

Safety Matters. (2025, November 22). The hidden danger in aerobatics: Understanding the push–pull effect. https://safetymatters.co.in%5Bsafetymatters%5D

Simple Wikipedia. (2025, November 20). 2025 HAL Tejas Dubai Air Show crash. https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/2025_HAL_Tejas_Dubai_Air_Show_crash%5Bwikipedia%5D

Singh, B., et al. (2011, June 29). Heart rate analysis during simulated push–pull effect manoeuvre. Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine. https://indjaerospacemed.com%5Bindjaerospacemed%5D

Sky Combat Ace. (2021, August 29). What is G‑LOC and how does it work? https://www.skycombatace.com%5Bskycombatace%5D

StatPearls. (2015, May 17). Aerospace gravitational effects. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430768/%5Bncbi.nlm.nih%5D

The Diplomat. (2025, December 1). Tejas crash in Dubai raises questions of fighter jet’s reliability. https://thediplomat.com%5Bthediplomat%5D

Times of India. (2025, November 21). Tejas fighter jet crashes during Dubai air show; eyewitness footage captures impact. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com%5Btimesofindia.indiatimes%5D

Reuters. (2025, November 21). Indian Tejas fighter jet crashes in a ball of fire at Dubai Airshow. https://www.reuters.com%5Breuters +1]

Leave a comment